So what is a triad? Well, it's like a dyad, but with three notes instead of two. Triads usually come in a common form, but do not have to. So to properly define a triad, it is a combination of three notes played in manner in which they end up sounding at the same time, that can be stacked into an arrangement of major, minor, augmented, and diminished thirds. This does not necessarily mean they are played at the same time, merely that they all sound together at some point. Technically they don't even need to sound together, but in close enough proximity that your ear's tonal memory interprets it all as cut from the same cloth, but that isn't really an important detail to remember at this time.

As per normal, we'll start with C Major.

This is a C Major triad. A chord chart will notate this as either CMaj or C. There are a few interesting things to note (haw) about the structure of this chord. Firstly, our root note is the tonic, C. Roots are just the same as they are in plants, the thingy at the bottom of the structure, be that note or delicious nutrition intake. Our second note is E, a major third up from the tonic. Our third note is G, a minor third up from the E, and a p5 up from C. Consequently, we can describe our chord structure as being 1-3-5. Now, while a p5 sounds like an empty restful interval, a C Major triad sounds full and restful. Your standard major triad possess a 1, which is to inform you which key the triad is in, and a 5, which gives you a good frame using the strength of the p5 interval. I feel like there are way too many commas in the previous sentence, perhaps I should start using ellipses? With this strong frame we add in a 3rd to color the chord. The 3rd, or something functioning like a 3rd, provides us with the needed color in any chord.

This is a C Major triad. A chord chart will notate this as either CMaj or C. There are a few interesting things to note (haw) about the structure of this chord. Firstly, our root note is the tonic, C. Roots are just the same as they are in plants, the thingy at the bottom of the structure, be that note or delicious nutrition intake. Our second note is E, a major third up from the tonic. Our third note is G, a minor third up from the E, and a p5 up from C. Consequently, we can describe our chord structure as being 1-3-5. Now, while a p5 sounds like an empty restful interval, a C Major triad sounds full and restful. Your standard major triad possess a 1, which is to inform you which key the triad is in, and a 5, which gives you a good frame using the strength of the p5 interval. I feel like there are way too many commas in the previous sentence, perhaps I should start using ellipses? With this strong frame we add in a 3rd to color the chord. The 3rd, or something functioning like a 3rd, provides us with the needed color in any chord. With this knowledge, can we then infer what the composition of a C minor chord is? Yes, yes we can. The only difference is the 3rd

. We can see this chord is hanging out in a very strange composition, since he was given a time signature, but not a double bar. A single minor chord doesn't make the most interesting harmonic motion, but hey I'm open to it if you are. Notice that from 1-3 we have an m3 and from 3-5 we now have an M3. Keeping that intervallic ratio works across any key, but you probably already knew that by now. Meaning that an Amin would be A-C-E.

. We can see this chord is hanging out in a very strange composition, since he was given a time signature, but not a double bar. A single minor chord doesn't make the most interesting harmonic motion, but hey I'm open to it if you are. Notice that from 1-3 we have an m3 and from 3-5 we now have an M3. Keeping that intervallic ratio works across any key, but you probably already knew that by now. Meaning that an Amin would be A-C-E.So returning to our CMaj chord for a bit here, remember how we talked about inversions a few lessons ago? This becomes much more interesting and important as it pertains to triads.

I have no idea why this image decided to go with half notes instead of the standard whole notes. On the left you can see the root position, with the C on the bottom like God and Jesus intended. Next to that we have first inversion, where they took the C and moved it to the top. Our chord is now E-G-C, but still functions like a CMaj chord. The root note is no longer on the bottom, but it still acts like a root in this chord, because if the chord was re-arranged it would be on the bottom. Looking at intervals, we have an m3 followed by a P4. Since there is no P5 in this chord (even though there might be one were the chord in root position), it is not as strong and decisive as if it were in root position. Additionally, the P5 isn't framing the 3rd, further weakening the chord. By weakening I mean that were you to hear this chord as the resolution of a build up of inevitability, it would not sound as satisfying as if the chord were in root position. Moving along, further on the right we have second inversion. First inversion is where the root is on the top of the chord, second inversion is where the root and 3rd are now on the top of the chord. Third, fourth, etc inversion exist when your chords have more notes in them. We can get to that later though. Second inversion has a P4, followed by an M3. Arguably this is stronger than first inversion because it has the M3, but not as strong as root position due to the lack of the previously mentioned. In practical use though, no one really cares. Both are weaker than root position, which is really what matters.

I have no idea why this image decided to go with half notes instead of the standard whole notes. On the left you can see the root position, with the C on the bottom like God and Jesus intended. Next to that we have first inversion, where they took the C and moved it to the top. Our chord is now E-G-C, but still functions like a CMaj chord. The root note is no longer on the bottom, but it still acts like a root in this chord, because if the chord was re-arranged it would be on the bottom. Looking at intervals, we have an m3 followed by a P4. Since there is no P5 in this chord (even though there might be one were the chord in root position), it is not as strong and decisive as if it were in root position. Additionally, the P5 isn't framing the 3rd, further weakening the chord. By weakening I mean that were you to hear this chord as the resolution of a build up of inevitability, it would not sound as satisfying as if the chord were in root position. Moving along, further on the right we have second inversion. First inversion is where the root is on the top of the chord, second inversion is where the root and 3rd are now on the top of the chord. Third, fourth, etc inversion exist when your chords have more notes in them. We can get to that later though. Second inversion has a P4, followed by an M3. Arguably this is stronger than first inversion because it has the M3, but not as strong as root position due to the lack of the previously mentioned. In practical use though, no one really cares. Both are weaker than root position, which is really what matters.Do inversions work the same in minor as they do in major? Yes.

We now have two good triads under our belt, which means we can talk about something a bit more complicated.

This is a C Diminished triad, or Cdim. Notice the diminished 5th interval. This is not a stable chord, and should never be used as a rest point unless you are writing something super weird or really know what you're doing. This is because of the natural tritone, it wants to pull itself apart into different chords. The strength of this chord is lessened with inversions, but not by much. There isn't really a good reason to know about the diminished triad at this point, but I'm covering it for completion purposes. This is similar to our next chord:

This is a C Diminished triad, or Cdim. Notice the diminished 5th interval. This is not a stable chord, and should never be used as a rest point unless you are writing something super weird or really know what you're doing. This is because of the natural tritone, it wants to pull itself apart into different chords. The strength of this chord is lessened with inversions, but not by much. There isn't really a good reason to know about the diminished triad at this point, but I'm covering it for completion purposes. This is similar to our next chord: The C Augmented triad! Notice that while the diminished triad had a minor third, the augmented triad has a major third, and the quality primarily comes from the 5th tone, which in this case is an augmented 5th. This chord is totally weird and you'll almost never see it. It sounds pretty cool and dissonant, and is better as a rest point than the diminished chord, but still isn't very good. It's also very hard to approach and resolve from, so it as an actual presence is exceptionally rare. I honestly haven't seen it much at all, and so anyone who can provide examples of it's use is more awesome than I.

The C Augmented triad! Notice that while the diminished triad had a minor third, the augmented triad has a major third, and the quality primarily comes from the 5th tone, which in this case is an augmented 5th. This chord is totally weird and you'll almost never see it. It sounds pretty cool and dissonant, and is better as a rest point than the diminished chord, but still isn't very good. It's also very hard to approach and resolve from, so it as an actual presence is exceptionally rare. I honestly haven't seen it much at all, and so anyone who can provide examples of it's use is more awesome than I. As I'm sure you can see, this is all a simple extension of the concepts covered in the previous lessons, and you can probably guess where things are going to go from here. Some intrepid soul might ask, "How come we don't take a C, add an augmented 3rd on top of that (F), and then another augmented 3rd? (B♭)" This would end you up with a chord that you could rearranged into F-B♭-C, which is another type of chord that isn't technically a triad, no matter how much I may have wanted to write about it. Basically there's a limit to how many ways you can rearrange chords and associate notes with eachother, and that configuration, although spread way out, would sound more like one thing than a triad, and would function as such. As always, questions & comments are appreciated.

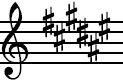

Wait, what's that F# doing on my staff? I thought I had topical cream for that. Anyways, that's a key signature! It tells you that when you see an F on the staff (in any position, not just that one), that it should be played as an F#, and not a regular F (or F♮, read as F natural). The natural sign, ♮, means that you should play a note that was augmented or diminished by some means (including key signature), in an un-augmented/diminished manner. G# becomes G, G♭ becomes G. Make sense? Back to key signatures, when you see a lonely F# next to your clef, that indicates that you are now in the key of G Major (this is not true, but we're running with it for now. Stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion!) (I like parentheses).

Wait, what's that F# doing on my staff? I thought I had topical cream for that. Anyways, that's a key signature! It tells you that when you see an F on the staff (in any position, not just that one), that it should be played as an F#, and not a regular F (or F♮, read as F natural). The natural sign, ♮, means that you should play a note that was augmented or diminished by some means (including key signature), in an un-augmented/diminished manner. G# becomes G, G♭ becomes G. Make sense? Back to key signatures, when you see a lonely F# next to your clef, that indicates that you are now in the key of G Major (this is not true, but we're running with it for now. Stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion!) (I like parentheses). We can see our F# in the same position before our C#, which is in its own position. These positions do not change in key signatures. The idea being by having them consistent its quick and easy to tell what key you are in. So this idea of moving by P5 (remember how important I told you it was?) seems to be working, so lets run with it.

We can see our F# in the same position before our C#, which is in its own position. These positions do not change in key signatures. The idea being by having them consistent its quick and easy to tell what key you are in. So this idea of moving by P5 (remember how important I told you it was?) seems to be working, so lets run with it. Here you can see the full list of sharps as they apply to key signatures. According to Wikipedia there is apparently a C# and G# major, but anyone playing in those is making their lives unreasonably difficult. Also according to Wikipedia, Miley Cyrus' 2009 smash hit "Party in the U.S.A." was written in F# Major. Ahh the wonders of technology.

Here you can see the full list of sharps as they apply to key signatures. According to Wikipedia there is apparently a C# and G# major, but anyone playing in those is making their lives unreasonably difficult. Also according to Wikipedia, Miley Cyrus' 2009 smash hit "Party in the U.S.A." was written in F# Major. Ahh the wonders of technology. Notice our B♭ there on the 3rd line, not giving a hoot about who sees him. Continuing on, you should be able to parse out the succession. I'll write it here for brevity. Major keys in increasing numbers of flats are B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The interesting thing here is that we have G♭ Major, which is nominally the same as F# Major, right? Yep! This is called enharmonic equivalence. A note that is enharmonic is one that is the same as another written representation. Sometimes people write stuff in G♭ Major, sometimes in F# Major, although people who write stuff in F# Major are clearly masochists who don't like playing in a proper key. Anecdotally, most classical musicians I know prefer the sharp keys, and most jazz musicians I know prefer the flat keys.

Notice our B♭ there on the 3rd line, not giving a hoot about who sees him. Continuing on, you should be able to parse out the succession. I'll write it here for brevity. Major keys in increasing numbers of flats are B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The interesting thing here is that we have G♭ Major, which is nominally the same as F# Major, right? Yep! This is called enharmonic equivalence. A note that is enharmonic is one that is the same as another written representation. Sometimes people write stuff in G♭ Major, sometimes in F# Major, although people who write stuff in F# Major are clearly masochists who don't like playing in a proper key. Anecdotally, most classical musicians I know prefer the sharp keys, and most jazz musicians I know prefer the flat keys. As you can see, it has 6 flats and is much neater and better organized than that stupid F# Major. I link that so you can see the organization of the flat key signatures.

As you can see, it has 6 flats and is much neater and better organized than that stupid F# Major. I link that so you can see the organization of the flat key signatures.  Wait a cotton pickin' minute! That looks like C Major! This is because A Minor is comprised entirely of natural notes too, and the scale simply starts on A instead of C. This is called relative minor, which is that every major scale has a relative minor scale, which shares key signatures. Remember how I said that the key signature meant we were in G Major, but that it wasn't actually true? This is why. When you notate these, the key signature only indicates that you're in one of the two, and whichever one it is does not actually matter. It will become clear because it will either center around the tonic of the major key or the tonic of the minor key.

Wait a cotton pickin' minute! That looks like C Major! This is because A Minor is comprised entirely of natural notes too, and the scale simply starts on A instead of C. This is called relative minor, which is that every major scale has a relative minor scale, which shares key signatures. Remember how I said that the key signature meant we were in G Major, but that it wasn't actually true? This is why. When you notate these, the key signature only indicates that you're in one of the two, and whichever one it is does not actually matter. It will become clear because it will either center around the tonic of the major key or the tonic of the minor key.

This is a perfect 5th. We can identify this in a couple ways. The easiest is to count note names: C, D, E, F, G. C is the first note, G is the last, there's a total of five. We can also count half steps (go ahead and count, I'll wait!), of which there are seven total. This is transitive across any dyad, it doesn't just work for C to G. The perfect fifth is one of the most important intervals there is, and has perfect consonance.

This is a perfect 5th. We can identify this in a couple ways. The easiest is to count note names: C, D, E, F, G. C is the first note, G is the last, there's a total of five. We can also count half steps (go ahead and count, I'll wait!), of which there are seven total. This is transitive across any dyad, it doesn't just work for C to G. The perfect fifth is one of the most important intervals there is, and has perfect consonance.  Before we discuss how it functions differently, lets talk about inversions again! The inversion of the P4 is, naturally, the P5 and vice versa (oh look, they add up to 9). This is good to keep in the back of your head, because the P5 will take a major center stage in the near future, while the P4 lies forgotten by the roadside, having to scrape together cash by begging on the street. Sure the P5 is going to occasionally kick some cash P4's way and they'll both pretend they're ok with how things have turned out but really P4 keeps on plugging away trying to make the chords work, while P5 is covetous of P4's laidback lifestyle. The main thing that's interesting about P4 is that it is a restful state when approached in one manner (Herbal Tea) and is in motion when approached in another (Coffee). Approached in this case means stuff played before we get to the the P4. This means that it possesses perfect consonance, as is required of a perfect interval, but can be used as dissonance when prepared properly. The reasons for this have to do with the harmonic series gobbletygook I posted about above and which I'll explain at some point.

Before we discuss how it functions differently, lets talk about inversions again! The inversion of the P4 is, naturally, the P5 and vice versa (oh look, they add up to 9). This is good to keep in the back of your head, because the P5 will take a major center stage in the near future, while the P4 lies forgotten by the roadside, having to scrape together cash by begging on the street. Sure the P5 is going to occasionally kick some cash P4's way and they'll both pretend they're ok with how things have turned out but really P4 keeps on plugging away trying to make the chords work, while P5 is covetous of P4's laidback lifestyle. The main thing that's interesting about P4 is that it is a restful state when approached in one manner (Herbal Tea) and is in motion when approached in another (Coffee). Approached in this case means stuff played before we get to the the P4. This means that it possesses perfect consonance, as is required of a perfect interval, but can be used as dissonance when prepared properly. The reasons for this have to do with the harmonic series gobbletygook I posted about above and which I'll explain at some point. . It's that line running perpendicular to the staff. Another example is

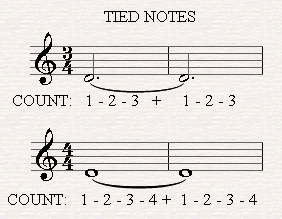

. It's that line running perpendicular to the staff. Another example is  which shows us two measures, and some other crap we're not covering in this lesson. What the measure does, in terms of function, is to divide your music up so that the beat delineation is easy to follow and notate. It ties directly into our concept of time signatures, so lets just get that out of the way too.

which shows us two measures, and some other crap we're not covering in this lesson. What the measure does, in terms of function, is to divide your music up so that the beat delineation is easy to follow and notate. It ties directly into our concept of time signatures, so lets just get that out of the way too.