So returning, as we so often do, to C. The first key that we will be looking at it is C Major, as it is the easiest, and who doesn't like easy? Hint, the answer is terrorists. So first off, what is a key? A key is a collection of tonal structures that surround the resting note, or tonic. The tonic is also the 1. In C Major, the tonic is C. So C Major is the collection of tonal structures that surround C. Keys come in a number of shapes and sizes, but we won't get into most of them until we cover a more advanced subject. For now, just know that there are Major keys and Minor keys. C Major and C Minor are similar in that they both are centered around C, but have totally different chord structures centered around them. Major keys are those which have the 3rd interval be a M3, Minor keys are those which have the 3rd interval be a m3. The 6th interval is also important to this concept, and follow suit being either M6 or m6, respectively. Every key possesses a Key Signature, which is some notation on the staff which denotes which key you are in (this makes it easier to read the music).

C Major's key signature is easy, it's totally blank. When we get into another key I'll discuss how to notate key signatures. For now, lets go about figuring out what intervals are present in C Major. By figuring this out, we then establish the C Major Scale. Remember, a scale is a sequential ordering of tones in a specific order, to produce a result. The chromatic scale being all tones present in an octave, any other scale must be a reduction of this. Traditional scales are of 7 notes(+ 1 at the octave), I'm not sure why. So if you've taken any beginning piano, you have played the C Major scale, its simply start on C, then play all white keys up to the next C. However we're erudite theoryographers, and we can break this down to a more useful format, so that we might play Major scales in other keys (I know, heresy).

The C Major Scale, in all its glory:

Exciting, no? So to analyze it, our first interval is M2, C to D, one whole step (or whole tone). Continuing on, we get another whole step, D - E. E - F is a half step (m2), then M2, M2, M2, m2. The cheater way to tell this is to watch the lady's key presses, the black keys are half steps (semitones). This ends us up with a pattern of "whole whole half whole whole whole half", in terms of step duration. Now you can play any major scale starting on any note. Simply follow the whole step & half step pattern. What does this net us in terms of overall intervals? M2, M3, P4, P5, M6, M7, P8. Easy now to see why this is a Major scale, huh? Now it is interesting to note that there is one other scale that falls into the concept of Major, but its quite a bit more advanced, so for all intents and purposes, this is the Major scale. Moving along by 5th, we head to G Major, which is the P5 of C

Major, for our next scale.

Wait, why did we move by P5? What's wrong with P4 or M2? Nothing at all, but P5 makes things easiest, as keys apply to a concept known as the Circle of Fifths or Cycle of Fifths. Those are synonyms, so don't get confused now. Why they follow this will become evident as we explore.

BEHOLD! G MAJOR!

Wait, what's that F# doing on my staff? I thought I had topical cream for that. Anyways, that's a key signature! It tells you that when you see an F on the staff (in any position, not just that one), that it should be played as an F#, and not a regular F (or F♮, read as F natural). The natural sign, ♮, means that you should play a note that was augmented or diminished by some means (including key signature), in an un-augmented/diminished manner. G# becomes G, G♭ becomes G. Make sense? Back to key signatures, when you see a lonely F# next to your clef, that indicates that you are now in the key of G Major (this is not true, but we're running with it for now. Stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion!) (I like parentheses).

Wait, what's that F# doing on my staff? I thought I had topical cream for that. Anyways, that's a key signature! It tells you that when you see an F on the staff (in any position, not just that one), that it should be played as an F#, and not a regular F (or F♮, read as F natural). The natural sign, ♮, means that you should play a note that was augmented or diminished by some means (including key signature), in an un-augmented/diminished manner. G# becomes G, G♭ becomes G. Make sense? Back to key signatures, when you see a lonely F# next to your clef, that indicates that you are now in the key of G Major (this is not true, but we're running with it for now. Stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion!) (I like parentheses).To figure out how this works, start on G and count your whole step/half step pattern. You come up with G, A, B, C, D, E....then you need a whole step to go from E. A whole step up from E is F#. That also lends us the half step needed to finish out the scale, as F# to G is a half step. Cool huh? Now, if C major had no sharps or flats, and G Major has 1 sharp, what logically follows as the key with 2 sharps?

That's right! It's D Major! Counting up a P5 again, we get to D from G. Once again, count your whole and half steps to figure out where the sharps lie. If you guessed that the sharps present were F# and C#, you would be correct. Wait, F is sharp AGAIN? Is it going to be sharp for all of these keys? Well, for all the sharp keys, yes it is. Sharp keys being ones that are defined by having sharps in their key signatures. Yes, there are flat keys too! So if F is going to be sharp for all subsequent keys, does that mean it needs to be present on every key signature? Yes it does! For simplicities sake, the F# is the first sharp on any sharp key signature.

BEHOLD! D MAJOR!

We can see our F# in the same position before our C#, which is in its own position. These positions do not change in key signatures. The idea being by having them consistent its quick and easy to tell what key you are in. So this idea of moving by P5 (remember how important I told you it was?) seems to be working, so lets run with it.

We can see our F# in the same position before our C#, which is in its own position. These positions do not change in key signatures. The idea being by having them consistent its quick and easy to tell what key you are in. So this idea of moving by P5 (remember how important I told you it was?) seems to be working, so lets run with it.Next up then is A Major, which has 3 sharps. After that is E Major, with 4 sharps, B Major with 5 sharps, and F# major with 6 sharps. F# major is extra special, for reasons we'll go into in a bit.

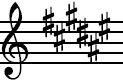

BEHOLD! F# MAJOR!

Here you can see the full list of sharps as they apply to key signatures. According to Wikipedia there is apparently a C# and G# major, but anyone playing in those is making their lives unreasonably difficult. Also according to Wikipedia, Miley Cyrus' 2009 smash hit "Party in the U.S.A." was written in F# Major. Ahh the wonders of technology.

Here you can see the full list of sharps as they apply to key signatures. According to Wikipedia there is apparently a C# and G# major, but anyone playing in those is making their lives unreasonably difficult. Also according to Wikipedia, Miley Cyrus' 2009 smash hit "Party in the U.S.A." was written in F# Major. Ahh the wonders of technology.Onwards and upwards, lets return to C. Now, that whole moving up by P5 was pretty exciting, but I think we can get more exciting by moving DOWN a P5. That takes us to our first flat key, F Major! Now using our same formula of half-step counting, lets look at how F Major works. F-G-A, uh oh we need a half step. A half step up from A is B♭. Why isn't it A#? Because it is functioning as the 4th interval (or 4th scale degree). We already have an A, so it has to be a B, which means its B♭. A whole step up from B♭ is C, and then we're back on track with D, E, F.

BEHOLD! F MAJOR!

Notice our B♭ there on the 3rd line, not giving a hoot about who sees him. Continuing on, you should be able to parse out the succession. I'll write it here for brevity. Major keys in increasing numbers of flats are B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The interesting thing here is that we have G♭ Major, which is nominally the same as F# Major, right? Yep! This is called enharmonic equivalence. A note that is enharmonic is one that is the same as another written representation. Sometimes people write stuff in G♭ Major, sometimes in F# Major, although people who write stuff in F# Major are clearly masochists who don't like playing in a proper key. Anecdotally, most classical musicians I know prefer the sharp keys, and most jazz musicians I know prefer the flat keys.

Notice our B♭ there on the 3rd line, not giving a hoot about who sees him. Continuing on, you should be able to parse out the succession. I'll write it here for brevity. Major keys in increasing numbers of flats are B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The interesting thing here is that we have G♭ Major, which is nominally the same as F# Major, right? Yep! This is called enharmonic equivalence. A note that is enharmonic is one that is the same as another written representation. Sometimes people write stuff in G♭ Major, sometimes in F# Major, although people who write stuff in F# Major are clearly masochists who don't like playing in a proper key. Anecdotally, most classical musicians I know prefer the sharp keys, and most jazz musicians I know prefer the flat keys.BEHOLD! G♭ MAJOR!

As you can see, it has 6 flats and is much neater and better organized than that stupid F# Major. I link that so you can see the organization of the flat key signatures.

As you can see, it has 6 flats and is much neater and better organized than that stupid F# Major. I link that so you can see the organization of the flat key signatures. So now we've spent a lot of time talking about Major keys, but none talking about Minor keys. So with Minor keys you don't start with C Minor, as it's a bit more complex. We start with A Minor.

BEHOLD! A MINOR!

Wait a cotton pickin' minute! That looks like C Major! This is because A Minor is comprised entirely of natural notes too, and the scale simply starts on A instead of C. This is called relative minor, which is that every major scale has a relative minor scale, which shares key signatures. Remember how I said that the key signature meant we were in G Major, but that it wasn't actually true? This is why. When you notate these, the key signature only indicates that you're in one of the two, and whichever one it is does not actually matter. It will become clear because it will either center around the tonic of the major key or the tonic of the minor key.

Wait a cotton pickin' minute! That looks like C Major! This is because A Minor is comprised entirely of natural notes too, and the scale simply starts on A instead of C. This is called relative minor, which is that every major scale has a relative minor scale, which shares key signatures. Remember how I said that the key signature meant we were in G Major, but that it wasn't actually true? This is why. When you notate these, the key signature only indicates that you're in one of the two, and whichever one it is does not actually matter. It will become clear because it will either center around the tonic of the major key or the tonic of the minor key. By starting on a different scale degree, we change the whole step and half step pattern, which makes the scale sound totally different. It is interesting to note that while there is one (technically two, ignore this for now) Major scale for a key, there are 3 Minor scales. If you were looking for a reductionist reason for why musicians are so whiny, this is probably as good a place to start as any. So our relative A Minor scale is the 'natural' minor scale. Natural minor is classified by having an m3, m6, m7.

It sounds like .

Please notice him play the scale for 2 octaves, and also horribly mispronounce Aeolian. He is correct that the natural minor scale is also called aeolian, but don't worry about that for now. Second on our minor scales is harmonic minor. It got this name because it was originally used purely to identify proper chord tones for use in harmonic structures. It has a somewhat exotic sound, because of its augmented second at the end (in A Minor F-G#). The only difference between it and natural minor is it possesses an M7 instead of an m7.

It sounds like this!

Please notice that the scale you care about comes about a minute in, and that he has completely idiotic opinions on the usage of the natural and melodic minor scales (being as that using the harmonic minor scale for a melody in the 1600s would likely get you burned at the stake). He does give some good information on the whole step/half step ratio, which I will cover down below.

Finally we come to the melodic minor scale, which is different going up than it is coming back down. On the ascent, it has the standard m3 (the main descriptor of a minor key), but it has a M6 and M7. On the descent, the 6 and 7 become m, so m6, m7, but the m3 is untouched. This scale was developed for melodic writing in the old traditional days, as ascending up to an M7 created good inevitability.

It sounds like .

Please note that I have no idea what the hell that dude is saying. Also notice that all of these minor key examples have guys saying "Deriving this from the major key is the easiest way". Now lets get to the whole and half steps.

Natural minor: whole half whole whole half whole whole

Harmonic minor: whole half whole whole half aug2 whole. Augmented second is a whole step + a half step.

Melodic minor: (ascent) whole half whole whole whole whole half (descent, think organized as coming down from the upper note) whole whole half whole whole half whole.

Ok! We now know our major and minor keys, key signatures, and scales! You should be able to identify your key signatures at a whim, and quickly discern what note I'm talking about if I say "4th scale degree of A♭ Major!". You understand some of why the P5 is such an important interval too. Most importantly, you now know what a tonic is. Trust me, that one is going to come up a bit. As always, questions and comments are welcomed.

No comments:

Post a Comment