As we all remember from lesson one, there were these things called whole notes and eighth notes and also this adjustable ratio dynamic between the two. To put this idea in perspective and have it start making practical sense, a few things need to be established. Most importantly is the time signature, but that's amusingly difficult to explain without explaining a lessor piece, the measure. Trust me on this one, I just tried.

The measure is a pretty easy concept, it divides your music into bits. Measures are also called bars by those hip young upstart jazz musicians, but I don't think their flailing is going to establish more than a brief foothold in the field of music. Now, if you'll excuse me, I need to adjust my powdered wig and write a scathing telegram stop. A measure looks like so

. It's that line running perpendicular to the staff. Another example is

. It's that line running perpendicular to the staff. Another example is  which shows us two measures, and some other crap we're not covering in this lesson. What the measure does, in terms of function, is to divide your music up so that the beat delineation is easy to follow and notate. It ties directly into our concept of time signatures, so lets just get that out of the way too.

which shows us two measures, and some other crap we're not covering in this lesson. What the measure does, in terms of function, is to divide your music up so that the beat delineation is easy to follow and notate. It ties directly into our concept of time signatures, so lets just get that out of the way too.The time signature looks like this

Now with all of this new information, I know you're just itching to blurt out all over the class and your sweatpants "But this would mean that a measure can contain exactly 1 whole note!!!!!!". And you would be completely correct. Not only that, but time signatures are usually designed to ensure that the whole note's duration spans the whole measure, but this is not always the case. At this point, we should probably cover what all of the different varieties of notes are.

The last two images I found didn't include the handy little text, and I'm not making images for you people. The last two being the 16th note and the 32nd note. Based on this pattern, can you guess what the 64th and 128h note look like? (Yes they exist, no you will likely never see them) Building on what we already know, we now know how to fill our measures with all sorts of interesting notes of varying durations. Part of the rule of a measure is that you can never exceed the total beat count per measure (otherwise the metric is totally useless) (second point, right now you should think about this as a single 'voice', or musical line. Please do not think about someone playing chords or anything more complicated, as you'll just get confused. All voices need to have their timing accounted for and have their parts add up to the total number of beats allowed in a measure). Sticking with 4/4 time, we can have 1 whole note per measure, 2 half notes, 4 quarter notes, 8 eighth notes, 16 sixteenth notes, and so on. The whole note will last for 4 beats, the half notes for 2, quarters for 1, and such. Math is hard, right?

A visual example for us to look at

So in the above link, disregard everything on the bottom line as that's some stupid guitar notation (called tablature) people came up with because they decided that would be easier than learning to read the already existing and comprehensive musical vocabulary that existed. If you know someone who wants to learn guitar, get them to understand the basics of real music notation, because tab does not transfer to other instruments. Guitar players who only learn tab do themselves a disservice if they ever want to do anything on a serious level besides "be in rock band".

So in that link, we see our staff, our trebel clef, our time signature of 4/4, and then we have a random quarter note all hanging out smoking marijuana cigarettes and lowering property values. He's called a pickup, and we can ignore him for now. Next we have a double bar, which you can see up above in our time signature example, and also in a few places around the link. A double bar indicates a stopping point, and is read with the thin line first. This first double bar we see indicates a stopping point for someone returning to the beginning. The thin bar being on the right means that we don't have to stop as we read the passage from right to left. When we encounter a double bar with the thin bar on the left, that indicates a stopping point (in this particular case, there are additional instructions, which we're going to ignore for later). So in our first true measure here, we have 4 eighth notes which are linked together (drawing all those tails gets tedious so you can just link 'em as pictured. To link 16th notes you just have 2 bars linking the notes instead of 1, etc down the line), which equates to two beats. Then we have a quarter note, so we're up to 3 beats, finishing off with 2 more eighth notes. Total beats for the measure: 4. Notice how the notes go sequentially. Time is notated horizontally. Notice the space between the quarter note and the subsequent eighth notes, as though if they wanted to put 2 eighth notes in there instead, they could and have the distances between the notes be the same? This is not necessary, but makes the thing a whole lot easier to read. If you have multiple lines, you should put notes that fall on the same beat on the same vertical plane (or as close to as possible, in certain circumstances) as possible.

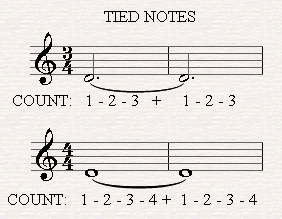

Finally, before we finish this one off, we need to discuss rests, dots and ties. Rests are an indicator to the musician not to play. These are notated in the exact same manner as notes, and last for the identical durations to their more notey counterparts. Here's a chart showing what they look like and how they line up. I also found this on the same website, which I think speaks for itself.

Also there are dots. Dots extend the duration of a note for 50% of the existing duration. In 4/4, our quarter note is one beat. A dotted quarter note is 1.5 beats, and it looks like this

EXAMPLE:

In the top example, we see 3/4 time (POP QUIZ WHAT DOES THAT MEAN), and then a dotted half note. A dotted half note would be 2 beats + 1 beat to equal 3 beats, filling out our measure. This note is then tied (that arc underneath the notes extending across the measure) to the other dotted half, meaning this is meant to be played as one note and then held for the duration of 6 beats. Below that we have the tied whole notes performing the same task in our 4/4 measure. The count bit there assumes you know how to count, and since (name of poster you don't like) is the only person on the site that isn't above a maturity level of 3 years old, I don't need to cover it. Now, in various cases within measures, you are not supposed to put dotted notes on 'off' beats (off beats are the beats between beats, in our guitar example from above the second eighth note is on an off beat, because it happens between where quarter notes would fall). You are especially not supposed to put dotted notes on off beats that cross the.....you know what? This one is full of enough information, I'm not going to confuse you guys any further.

Ok so this one has a lot more information in it, and while I've tried to be as clear as possible, some of this could be pretty confusing because there's lots of "ignore this bit for now" stuff. If you have any questions, post them and I'll answer when I can, probably will be able to tomorrow. If you do not understand stuff that is covered here you will have a lot of difficulty in upcoming posts, so no matter how stupid you think the question is, ask it.

No comments:

Post a Comment