Solfege is the process of assigning syllables to musical notes so that you aren't singing a melody without words as 1-4-5-3-6-3-5-1 or something like that. The system is pretty well known due to that song from the sound of music, but most people don't know how to do half steps with it. Nor are they necessarily competent at actually singing in the appropriate tones. There are two systems which assign solfege syllables, called the movable do system and the fixed do system (do is pronounced the same as dough). The fixed do system is primarily (to my understanding) used in Europe, and since Europe is full of communists and terrorists, we will not be using it.

The movable do system is a pretty easy concept, it simply means that the syllable do, attributed to the tonic in the established key, is dynamic. If you are in the key of E, the E is do. Key of F, F is do and so on. The fixed do system has each note on the keyboard assigned to the same syllable every time. I think do is always C, but I'm not sure because I'M A RED BLOODED AMERICAN ALL I EAT IS STEAK. I prefer the movable do system on principal just because it is much more clearly demonstrable to the relationships between the various notes than the fixed do system is. Let us remember our chromatic scale now!

Let us now assume for the sake of argument that we're in the key of C Major, I see no key signature so its a pretty safe assumption. C is therefore Do. Moving along, we continue up the C Major scale first with the basic syllables. C = Do, D = Re, E = Mi, F = Fa, G = Sol, A = La, B = Ti. These are pronounced Dough, Ray, Me, Fah, Soul, Lah, Tee. Now we shall look at the chromatic syllables. Like the melodic minor scale, this differs depending on whether you are ascending or descending. Notice a theme? I'm going to include pronunciations in parentheses next to the syllables.

Ascending: Do, Di(dee), Re, Ri(ree), Mi, Fa, Fi(fee), Sol, Si(see), La, Li(lee), Ti, Do!

Descending: Do, Ti, Te(tay), La, Le(lay), Sol, Se(say), Fa, Mi, Me(may), Re, Ra(Rah), Do.

Please notice that the flat 2 when descending is Ra, the glorious god of the sun! I'm sure you were on pins and needles waiting for him to show up since he stood you up at the bar last week. To get these really cemented in your head I seriously recommend singing a few chromatic scales with the syllables until you get it so you embed the ratios in your brain.

So lets do some listening here to analyze what we're doing. To start, we will use Mary Had a Little Lamb, which is a little ditty that most people are taught when they initially learn how to play the piano.

I chose this selection because it was somehow less annoying than the other example I found. I'm still not quite sure how this works. Listening to our melody, which is sung by a totally kawaii girl ^_^, we can analyze as being 3-2-1-2-3-3-3, 2-2-2, 3-5-5 etc. Or: Mi re do re mi mi mi, re re re, mi sol sol, mi re do re mi mi mi mi re re mi re do.

Ok! That was easy, so lets get a bit more complicated. Here is a series of scores by Robert Schumann (you may need to click a link to get them to let you open the page), and here are the associated works so that you can listen along. Let us examine Melodie first.

First off, notice C in place of the time signature. That indicates Common Time, or 4/4. Secondly, notice that the bottom staff on our grand staff is also in the trebel clef. Finally, those 2 dots in the 4th measure indicate that you are to repeat those 4 measures one time before moving on. Our melody, which is always the topmost note in this case (but that is not always true), starts off with mi re do ti la do ti re do sol. It then continues with sol fa mi do ti la sol. About the only other thing of note with this work is the use of the natural sign in the 8th bar, to cancel out the sharp C in the bass line.

Soldatenmarsch just below it is also a good example to look at, and will help us examine the movable do system a bit. The melody is on top as per usual. We have a couple clef changes in the bass too, but we don't really care about that so much. Starting on B, we go mi fa sol la sol fa mi re do, mi fa sol la sol do ti la sol, then that line repeats. Skipping down to the next set of lines, right after our repeat sign that's facing to the right (meaning when you are directed to repeat a passage, you go back to that sign and begin there), sol la ti la sol la sol fa mi, now this gets interesting. Our melody is briefly transferred to the bass note, as we have a nice little chord here, then back to the top notes. Notice how, when we go up an octave, the syllable does not change. This is a limitation of the system.

For my last example, we're going to get considerably more elaborate. I've had a hell of a time finding decent examples that have sheet music too, such that you can follow along. But I found something that's more complicated than what we've done, and is a song everyone should know because it is awesome.

And the transcribed solo is here. We're going to be looking at Miles Davis' solo for this song, which starts at about 2:13 or so. Take a couple listens to it so that you're familiar with what he plays. Notice our key is Bflat, so we'll use that as our do. Also please notice that the eighth notes are not played in a strictly even fashion, this is a stylistic choice present in jazz known as swung eighth notes. More on that later.

Easy enough, we start out with do do do. A couple rests, then la do la li re. La do me fa me la. Do te te re la sol. Ti la ti la sol la ti do sol la li fa. Le do mi sol sol te la la fa.

And so on. Feel free to poke through the rest of it. Please notice that context is important for the syllables. In general when a passage is ascending you use the ascending ones, and vice versa. In the case of the me in the 3rd group, it functions as a flat 3 in that passage due to the tones surrounding it, this will make more sense in subsequent lessons. The te at the very end is approached through an ascent, but is then used as part of a descending phrase, and is thus more applicable to the 7th than a raised 6th. Fudging it is ok though, no one is going to yell at you for using the wrong syllable.

I feel like this lesson is somewhat lackluster, but it should give some general grounding about how to interact with intervals. Thanks as always.

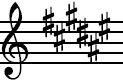

Wait, what's that F# doing on my staff? I thought I had topical cream for that. Anyways, that's a key signature! It tells you that when you see an F on the staff (in any position, not just that one), that it should be played as an F#, and not a regular F (or F♮, read as F natural). The natural sign, ♮, means that you should play a note that was augmented or diminished by some means (including key signature), in an un-augmented/diminished manner. G# becomes G, G♭ becomes G. Make sense? Back to key signatures, when you see a lonely F# next to your clef, that indicates that you are now in the key of G Major (this is not true, but we're running with it for now. Stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion!) (I like parentheses).

Wait, what's that F# doing on my staff? I thought I had topical cream for that. Anyways, that's a key signature! It tells you that when you see an F on the staff (in any position, not just that one), that it should be played as an F#, and not a regular F (or F♮, read as F natural). The natural sign, ♮, means that you should play a note that was augmented or diminished by some means (including key signature), in an un-augmented/diminished manner. G# becomes G, G♭ becomes G. Make sense? Back to key signatures, when you see a lonely F# next to your clef, that indicates that you are now in the key of G Major (this is not true, but we're running with it for now. Stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion!) (I like parentheses). We can see our F# in the same position before our C#, which is in its own position. These positions do not change in key signatures. The idea being by having them consistent its quick and easy to tell what key you are in. So this idea of moving by P5 (remember how important I told you it was?) seems to be working, so lets run with it.

We can see our F# in the same position before our C#, which is in its own position. These positions do not change in key signatures. The idea being by having them consistent its quick and easy to tell what key you are in. So this idea of moving by P5 (remember how important I told you it was?) seems to be working, so lets run with it. Here you can see the full list of sharps as they apply to key signatures. According to Wikipedia there is apparently a C# and G# major, but anyone playing in those is making their lives unreasonably difficult. Also according to Wikipedia, Miley Cyrus' 2009 smash hit "Party in the U.S.A." was written in F# Major. Ahh the wonders of technology.

Here you can see the full list of sharps as they apply to key signatures. According to Wikipedia there is apparently a C# and G# major, but anyone playing in those is making their lives unreasonably difficult. Also according to Wikipedia, Miley Cyrus' 2009 smash hit "Party in the U.S.A." was written in F# Major. Ahh the wonders of technology. Notice our B♭ there on the 3rd line, not giving a hoot about who sees him. Continuing on, you should be able to parse out the succession. I'll write it here for brevity. Major keys in increasing numbers of flats are B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The interesting thing here is that we have G♭ Major, which is nominally the same as F# Major, right? Yep! This is called enharmonic equivalence. A note that is enharmonic is one that is the same as another written representation. Sometimes people write stuff in G♭ Major, sometimes in F# Major, although people who write stuff in F# Major are clearly masochists who don't like playing in a proper key. Anecdotally, most classical musicians I know prefer the sharp keys, and most jazz musicians I know prefer the flat keys.

Notice our B♭ there on the 3rd line, not giving a hoot about who sees him. Continuing on, you should be able to parse out the succession. I'll write it here for brevity. Major keys in increasing numbers of flats are B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭. The interesting thing here is that we have G♭ Major, which is nominally the same as F# Major, right? Yep! This is called enharmonic equivalence. A note that is enharmonic is one that is the same as another written representation. Sometimes people write stuff in G♭ Major, sometimes in F# Major, although people who write stuff in F# Major are clearly masochists who don't like playing in a proper key. Anecdotally, most classical musicians I know prefer the sharp keys, and most jazz musicians I know prefer the flat keys. As you can see, it has 6 flats and is much neater and better organized than that stupid F# Major. I link that so you can see the organization of the flat key signatures.

As you can see, it has 6 flats and is much neater and better organized than that stupid F# Major. I link that so you can see the organization of the flat key signatures.  Wait a cotton pickin' minute! That looks like C Major! This is because A Minor is comprised entirely of natural notes too, and the scale simply starts on A instead of C. This is called relative minor, which is that every major scale has a relative minor scale, which shares key signatures. Remember how I said that the key signature meant we were in G Major, but that it wasn't actually true? This is why. When you notate these, the key signature only indicates that you're in one of the two, and whichever one it is does not actually matter. It will become clear because it will either center around the tonic of the major key or the tonic of the minor key.

Wait a cotton pickin' minute! That looks like C Major! This is because A Minor is comprised entirely of natural notes too, and the scale simply starts on A instead of C. This is called relative minor, which is that every major scale has a relative minor scale, which shares key signatures. Remember how I said that the key signature meant we were in G Major, but that it wasn't actually true? This is why. When you notate these, the key signature only indicates that you're in one of the two, and whichever one it is does not actually matter. It will become clear because it will either center around the tonic of the major key or the tonic of the minor key.

This is a perfect 5th. We can identify this in a couple ways. The easiest is to count note names: C, D, E, F, G. C is the first note, G is the last, there's a total of five. We can also count half steps (go ahead and count, I'll wait!), of which there are seven total. This is transitive across any dyad, it doesn't just work for C to G. The perfect fifth is one of the most important intervals there is, and has perfect consonance.

This is a perfect 5th. We can identify this in a couple ways. The easiest is to count note names: C, D, E, F, G. C is the first note, G is the last, there's a total of five. We can also count half steps (go ahead and count, I'll wait!), of which there are seven total. This is transitive across any dyad, it doesn't just work for C to G. The perfect fifth is one of the most important intervals there is, and has perfect consonance.  Before we discuss how it functions differently, lets talk about inversions again! The inversion of the P4 is, naturally, the P5 and vice versa (oh look, they add up to 9). This is good to keep in the back of your head, because the P5 will take a major center stage in the near future, while the P4 lies forgotten by the roadside, having to scrape together cash by begging on the street. Sure the P5 is going to occasionally kick some cash P4's way and they'll both pretend they're ok with how things have turned out but really P4 keeps on plugging away trying to make the chords work, while P5 is covetous of P4's laidback lifestyle. The main thing that's interesting about P4 is that it is a restful state when approached in one manner (Herbal Tea) and is in motion when approached in another (Coffee). Approached in this case means stuff played before we get to the the P4. This means that it possesses perfect consonance, as is required of a perfect interval, but can be used as dissonance when prepared properly. The reasons for this have to do with the harmonic series gobbletygook I posted about above and which I'll explain at some point.

Before we discuss how it functions differently, lets talk about inversions again! The inversion of the P4 is, naturally, the P5 and vice versa (oh look, they add up to 9). This is good to keep in the back of your head, because the P5 will take a major center stage in the near future, while the P4 lies forgotten by the roadside, having to scrape together cash by begging on the street. Sure the P5 is going to occasionally kick some cash P4's way and they'll both pretend they're ok with how things have turned out but really P4 keeps on plugging away trying to make the chords work, while P5 is covetous of P4's laidback lifestyle. The main thing that's interesting about P4 is that it is a restful state when approached in one manner (Herbal Tea) and is in motion when approached in another (Coffee). Approached in this case means stuff played before we get to the the P4. This means that it possesses perfect consonance, as is required of a perfect interval, but can be used as dissonance when prepared properly. The reasons for this have to do with the harmonic series gobbletygook I posted about above and which I'll explain at some point. . It's that line running perpendicular to the staff. Another example is

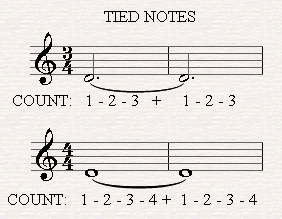

. It's that line running perpendicular to the staff. Another example is  which shows us two measures, and some other crap we're not covering in this lesson. What the measure does, in terms of function, is to divide your music up so that the beat delineation is easy to follow and notate. It ties directly into our concept of time signatures, so lets just get that out of the way too.

which shows us two measures, and some other crap we're not covering in this lesson. What the measure does, in terms of function, is to divide your music up so that the beat delineation is easy to follow and notate. It ties directly into our concept of time signatures, so lets just get that out of the way too.

Five lines, no frills, tells us nothing. In order to know what those lines mean, at the beginning of each staff there is a a symbol called a clef. There are three types of clefs:

Five lines, no frills, tells us nothing. In order to know what those lines mean, at the beginning of each staff there is a a symbol called a clef. There are three types of clefs:  Bass

Bass  and Movable C.

and Movable C..jpg%22)

which is notable in that it combines the two previously discussed clefs in one easy to read format. Notice the little bracket on the far left binding the two staves and associated clefs together. The clefs define which notes are what on the staff. Our staff needs notes, which are usually represented by circles, and circles with lines coming off of them.

which is notable in that it combines the two previously discussed clefs in one easy to read format. Notice the little bracket on the far left binding the two staves and associated clefs together. The clefs define which notes are what on the staff. Our staff needs notes, which are usually represented by circles, and circles with lines coming off of them.  Look familiar? These are called eighth notes, and they determine the length in which the note is played, but we don't really care about that for the purposes of this discussion. What we care about is what tones the notes represent, and to get to that involves a sidetrack, which will be covered in a subsequent post (I was about halfway through writing all of this and realized that it was probably getting to be a bit much for a first post).

Look familiar? These are called eighth notes, and they determine the length in which the note is played, but we don't really care about that for the purposes of this discussion. What we care about is what tones the notes represent, and to get to that involves a sidetrack, which will be covered in a subsequent post (I was about halfway through writing all of this and realized that it was probably getting to be a bit much for a first post).